The History of Abaco in the Bahamas

In 1492 Columbus made his first landfall in The Bahamas on the island he named San Salvador. That and the other islands he visited are 200 miles southeast of Abaco, shown on a Spanish map from 1500 as “Habacoa,” an Indian word.

The Spanish enslaved the Lucayan Indians in the early 1500s, and the rest likely died from disease. Many artifacts have been found on Abaco, both on land and underwater in blue holes that dot the landscape. The island was said to have had a large Indian population, numbering in the thousands.

After the Indians, the island remained unpopulated for over 150 years except for a short lived French settlement that “may” have been located on southern Abaco and a legendary Portuguese whaling station. Ruins located there were originally attributed to the French, but are now believed to be from the Loyalist period. During that time the Spanish plied the waters around Abaco salvaging ships that had sunk along the ragged ocean reefs and scavenging anything they could find or kill on shore (native monk seals were common and could render oil). In the mid-1600s sailing vessels from Eleuthera and Harbour Island worked the wrecks along the coast, but Abaco wasn’t settled by British Loyalists until after the American Revolutionary War.

The first European settlement on Abaco was a group of some 1,000 Loyalists from New York. “Loyalists” were families that remained faithful to King George III during the American Revolution, suffering the social consequences when England lost to the new Americans who were happy to run them out of their new nation. The settlement they began was named “Carleton” after Sir Guy Carleton, the British Commander in New York City before it was turned over to the Americans. They soon established “Marsh’s Harbour,” today the main town and only traffic light in Abaco.

Early settlers had it tough. Farming in The Bahamas is difficult on the rocky terrain with thin topsoil that is easily depleted of nutrients. It was not what they were accustomed to in America and eventually Carleton was abandoned as many of the early settlers turned to the sea for their livelihoods. This led many to settle the barrier islands on the north side of Abaco Sound where fishing, boat building and wreck salvaging became more important than farming.

The Sea of Abaco and the barrier reefs were full of fish, turtles, conch and crawfish (lobster), which provided the protein base for the settlers supplemented by vegetables grown in home gardens on the islands. However, there was little to export since cotton, tobacco and other crops failed on mainland Abaco as they did all over The Bahamas in the 1800s. British Emancipation occurred in 1834 which freed the Loyalist’s slaves, some of whom left to start their own settlements on Abaco. This didn’t help matters as the traditional plantation model slipped away.

Part of living off the sea meant “wrecking,” which meant salvaging cargo from vessels that wrecked on the reefs off the northern and eastern shores. Wrecks were profitable and there is a story about a preacher who set his congregation up with their backs to the sea so he’d be the first notice if a ship grounded on the reef beyond. Whether true or not, it illustrates the importance wrecking once had.

There are also nefarious stories of false lights being set at night to lure ships onto the reefs so they could “save” the crew and salvage the cargo. Shipwrecks were common and there were objections to the lighthouse that was eventually built in Hopetown by the British Imperial Lighthouse Service in 1864. It must have been frustrating to see all the precious cargo pass by your struggling town on ships offshore, why not lure a few onto the reef!

There was a brief period of prosperity in The Bahamas during the Civil War, but most of that occurred in Nassau as cotton and other goods from the American South were traded for European munitions and supplies needed to sustain the Confederacy. A few ship wrecks during that period occurred on the Abaco reef, including the Adirondack and San Jacinto, both Union ships whose remains can still be seen snorkeling today.

Sponging, pineapples and citrus were important industries in the 1800s and sisal (used for making rope and less dependent on good soil) was added to the mix, but life was still tough on Abaco. Boat building continued through the tough times and many fine ships were launched in Abaco built from hardwoods that could be found around the islands like lignum vitae, horseflesh, mahogany and Abaco pine. Many smaller Abaco skiffs were built to run about the sound and Abaco designs endure to this day.

The pine forests of Abaco are vast, growing over a large freshwater aquifer. In 1908 the logging town of Wilson City sprang up at the east end of Abaco Sound. The city had electricity, giving Abaco that modern wonder the same time as Nassau. In 1923 regular mail boat service from Nassau came to Abaco with the diesel powered Priscilla. Telegraph service to Hopetown was added and Abaco began to open up to the world after 140 years of remote isolation since the establishment of Carleton. Prohibition and rum running brought another boom to The Bahamas but again it was relegated mainly to Nassau and the Bahamian islands closest to Florida.

Crawfish exports to America began in the mid-1930s, local boats hauling them to Florida in live wells. Today commercial crawfish boats from Abaco can be seen as far away as the Cay Sal Bank off Cuba.

Several Abaco men went to serve in World War II while German submarines cruised the international shipping lanes north of Abaco. After the war, Bahamas Airways began seaplane service to Nassau using war vintage Catalinas along with Grumman Gooses. Abaco native Leonard Thompson played a big role in this, and seaplane service continued until the airport in Marsh Harbour went into service in the early 1960s. Thompson also played a major role in the development of Treasure Cay.

Little Harbour marks the eastern end of Abaco Sound and features the Johnston Art Foundry, a bronze casting studio founded by Randolph Johnston in the 1950s where many famous works have been created.

In 1958 Marcell Albury of Man-O-War started Albury Ferry Service which now connects many of the islands to the Abaco mainland for residents and tourists. Nothing is more relaxing than climbing aboard a comfortable ferry as you make your way to beautiful, historic communities like Hope Town on Elbow Cay and New Plymouth on Green Turtle Cay.

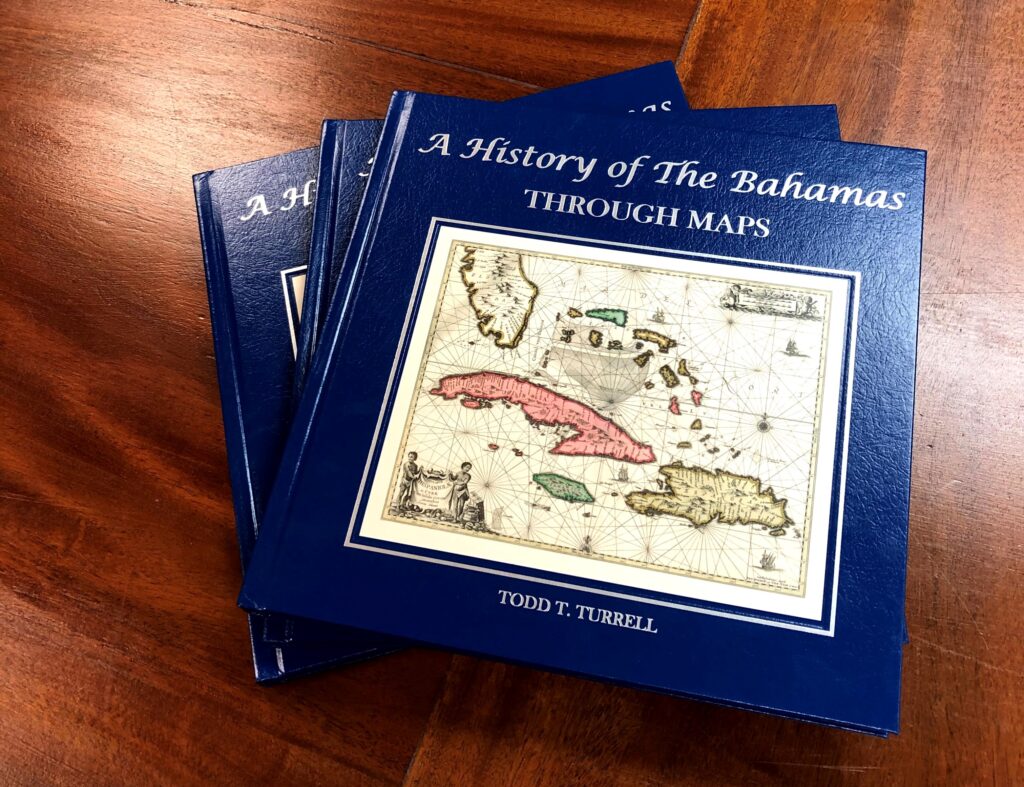

To learn more about history of Abaco and other islands in the Bahamas, check out A History of The Bahamas Through Maps. The book and custom map of Abaco Island can be purchased online at this website. Questions? Please call us at 239-963-3497.