Shipwrecks and The Florida Keys

Shipwrecks have been a way of life in the Keys since Europeans first arrived in the New World. The long reef system rose up from the Gulfstream to catch ships off guard since the low islands of the Keys were hard to see until it was too late. In the days of sail, ships could be blown up on the reef tearing out their bottoms and sinking them in often violent seas.

Early shipwreck survivors could expect harsh treatment ashore from the Native American Indians. They were typically killed on the spot or enslaved and traded up the coast. A 13 year old Spaniard, Hernando Fontaneda, was shipwrecked in the Keys in 1549 and assimilated into the Calusa Indian tribe where he learned their language. He was rescued 20 years later in southwest Florida and in 1571 wrote about his experience, providing a rare glimpse into Florida’s ancient Indian culture. By the late 1600s the Indians were Spanish allies helping them salvage their wrecks. Shipwrecks along the Keys reef plagued the Spanish and treasure fleets were lost in 1622 and 1733.

The famous galleon Atocha, salvaged by Mel Fisher in 1985, was lost in the 1622 fleet. Wrecks provided an era of prosperity in Key West which became the largest and wealthiest Florida city in the mid 1800s when ships sank on the reef almost daily, their cargos salvaged by Keys “Wreckers” and auctioned off in Key West.

The wrecking industry faded away as lighthouses were built and ships changed from sail to steam, greatly improving their ability to avoid the treacherous reef.

Many shipwrecks can still be seen today on the reef by snorkeling shallow wreck sites or scuba diving on deeper ones.

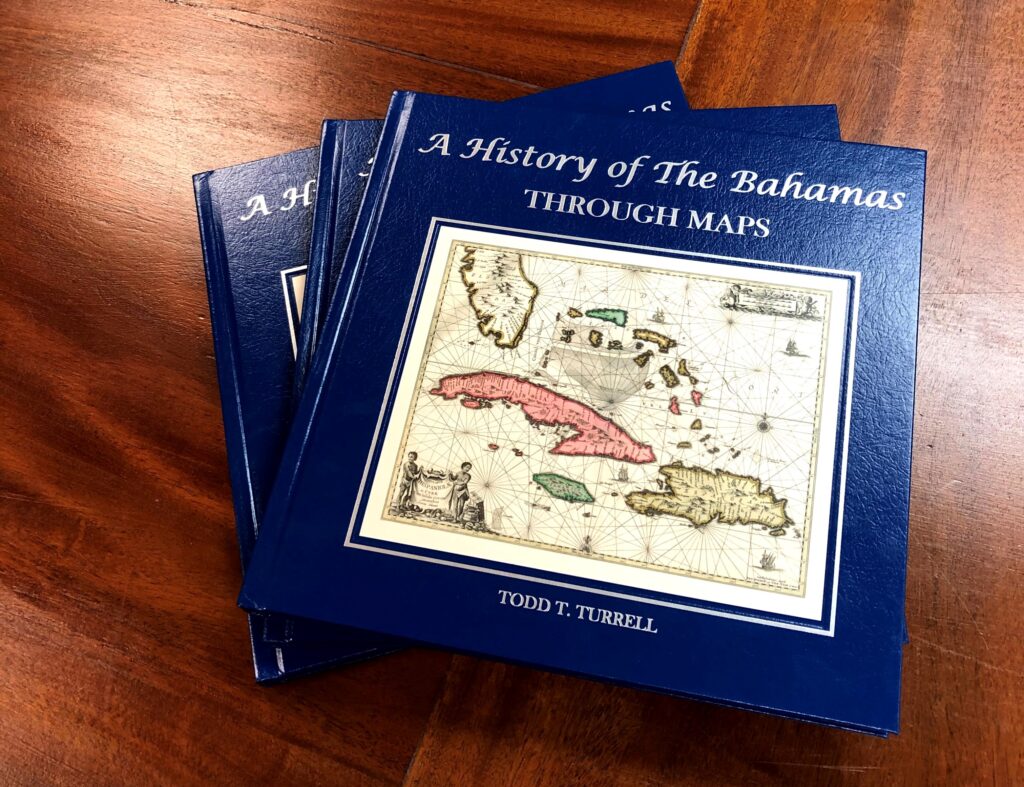

To learn more about the Florida Keys check out our latest book The Florida Keys: A History Through Maps. Call today for questions regarding custom orders of maps and many other products, 239-963-3497!

Artistic maps that invoke your favorite memories.

Whether it’s an 18″ x 24″ glossy poster or a 32″ x 42″ extra large fine art canvas, our maps are conversation starters and the perfect launching pad for your best stories.